democracy depends on the consent of the losers. For most of the 20th century, parties and candidates in the United States have competed in elections with the understanding that electoral defeats are neither permanent nor intolerable. The losers could accept the result, adjust their ideas and coalitions, and move on to fight in the next election. Ideas and policies would be contested, sometimes viciously, but however heated the rhetoric got, defeat was not generally equated with political annihilation. The stakes could feel high, but rarely existential. In recent years, however, beginning before the election of Donald Trump and accelerating since, that has changed.

To hear more feature stories, see our full list or get the Audm iPhone app.

"Our radical Democrat opponents are driven by hatred, prejudice, and rage," Trump told the crowd at his reelection kickoff event in Orlando in June. "They want to destroy you and they want to destroy our country as we know it." This is the core of the president's pitch to his supporters: He is all that stands between them and the abyss.

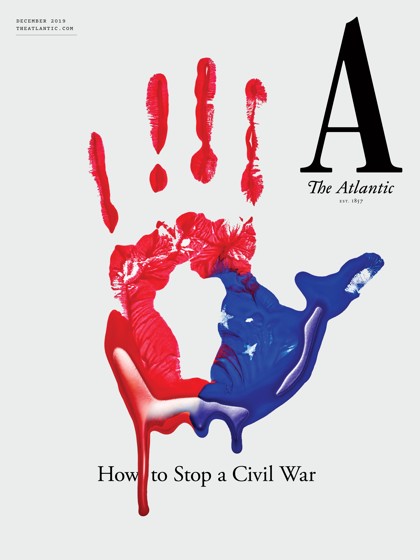

In October, with the specter of impeachment looming, he fumed on Twitter, "What is taking place is not an impeachment, it is a COUP, intended to take away the Power of the People, their VOTE, their Freedoms, their Second Amendment, Religion, Military, Border Wall, and their God-given rights as a Citizen of The United States of America!" For good measure, he also quoted a supporter's dark prediction that impeachment "will cause a Civil War like fracture in this Nation from which our Country will never heal."

Trump's apocalyptic rhetoric matches the tenor of the times. The body politic is more fractious than at any time in recent memory. Over the past 25 years, both red and blue areas have become more deeply hued, with Democrats clustering in cities and suburbs and Republicans filling in rural areas and exurbs. In Congress, where the two caucuses once overlapped ideologically, the dividing aisle has turned into a chasm.

As partisans have drifted apart geographically and ideologically, they've become more hostile toward each other. In 1960, less than 5 percent of Democrats and Republicans said they'd be unhappy if their children married someone from the other party; today, 35 percent of Republicans and 45 percent of Democrats would be, according to a recent Public Religion Research Institute/Atlantic poll—far higher than the percentages that object to marriages crossing the boundaries of race and religion. As hostility rises, Americans' trust in political institutions, and in one another, is declining. A study released by the Pew Research Center in July found that only about half of respondents believed their fellow citizens would accept election results no matter who won. At the fringes, distrust has become centrifugal: Right-wing activists in Texas and left-wing activists in California have revived talk of secession.

Recent research by political scientists at Vanderbilt University and other institutions has found both Republicans and Democrats distressingly willing to dehumanize members of the opposite party. "Partisans are willing to explicitly state that members of the opposing party are like animals, that they lack essential human traits," the researchers found. The president encourages and exploits such fears. This is a dangerous line to cross. As the researchers write, "Dehumanization may loosen the moral restraints that would normally prevent us from harming another human being."

Outright political violence remains considerably rarer than in other periods of partisan divide, including the late 1960s. But overheated rhetoric has helped radicalize some individuals. Cesar Sayoc, who was arrested for targeting multiple prominent Democrats with pipe bombs, was an avid Fox News watcher; in court filings, his lawyers said he took inspiration from Trump's white-supremacist rhetoric. "It is impossible," they wrote, "to separate the political climate and [Sayoc's] mental illness." James Hodgkinson, who shot at Republican lawmakers (and badly wounded Representative Steve Scalise) at a baseball practice, was a member of the Facebook groups Terminate the Republican Party and The Road to Hell Is Paved With Republicans. In other instances, political protests have turned violent, most notably in Charlottesville, Virginia, where a Unite the Right rally led to the murder of a young woman. In Portland, Oregon, and elsewhere, the left-wing "antifa" movement has clashed with police. The violence of extremist groups provides ammunition to ideologues seeking to stoke fear of the other sidexWhat has caused such rancor? The stresses of a globalizing, postindustrial economy. Growing economic inequality. The hyperbolizing force of social media. Geographic sorting. The demagogic provocations of the president himself. As in Murder on the Orient Express, every suspect has had a hand in the crime.

But the biggest driver might be demographic change. The United States is undergoing a transition perhaps no rich and stable democracy has ever experienced: Its historically dominant group is on its way to becoming a political minority—and its minority groups are asserting their co-equal rights and interests. If there are precedents for such a transition, they lie here in the United States, where white Englishmen initially predominated, and the boundaries of the dominant group have been under negotiation ever since. Yet those precedents are hardly comforting. Many of these renegotiations sparked political conflict or open violence, and few were as profound as the one now under way.

FROM OUR DECEMBER 2019 ISSUE

Subscribe to The Atlantic and support 160 years of independent journalism

SubscribeWithin the living memory of most Americans, a majority of the country's residents were white Christians. That is no longer the case, and voters are not insensate to the change—nearly a third of conservatives say they face "a lot" of discrimination for their beliefs, as do more than half of white evangelicals. But more epochal than the change that has already happened is the change that is yet to come: Sometime in the next quarter century or so, depending on immigration rates and the vagaries of ethnic and racial identification, nonwhites will become a majority in the U.S. For some Americans, that change will be cause for celebration; for others, it may pass unnoticed. But the transition is already producing a sharp political backlash, exploited and exacerbated by the president. In 2016, white working-class voters who said that discrimination against whites is a serious problem, or who said they felt like strangers in their own country, were almost twice as likely to vote for Trump as those who did not. Two-thirds of Trump voters agreed that "the 2016 election represented the last chance to stop America's decline." In Trump, they'd found a defender.

in 2002, the political scientist Ruy Teixeira and the journalist John Judis published a book, The Emerging Democratic Majority, which argued that demographic changes—the browning of America, along with the movement of more women, professionals, and young people into the Democratic fold—would soon usher in a "new progressive era" that would relegate Republicans to permanent minority political status. The book argued, somewhat triumphally, that the new emerging majority was inexorable and inevitable. After Barack Obama's reelection, in 2012, Teixeira doubled down on the argument in The Atlantic, writing, "The Democratic majority could be here to stay." Two years later, after the Democrats got thumped in the 2014 midterms, Judis partially recanted, saying that the emerging Democratic majority had turned out to be a mirage and that growing support for the GOP among the white working class would give the Republicans a long-term advantage. The 2016 election seemed to confirm this.

But now many conservatives, surveying demographic trends, have concluded that Teixeira wasn't wrong—merely premature. They can see the GOP's sinking fortunes among younger voters, and feel the culture turning against them, condemning them today for views that were commonplace only yesterday. They are losing faith that they can win elections in the future. With this come dark possibilities.

The United States is undergoing a transition perhaps no rich and stable democracy has ever experienced: Its historically dominant group is on its way to becoming a political minority.The Republican Party has treated Trump's tenure more as an interregnum than a revival, a brief respite that can be used to slow its decline. Instead of simply contesting elections, the GOP has redoubled its efforts to narrow the electorate and raise the odds that it can win legislative majorities with a minority of votes. In the first five years after conservative justices on the Supreme Court gutted a key provision of the Voting Rights Act in 2013, 39 percent of the counties that the law had previously restrained reduced their number of polling places. And while gerrymandering is a bipartisan sin, over the past decade Republicans have indulged in it more heavily. In Wisconsin last year, Democrats won 53 percent of the votes cast in state legislative races, but just 36 percent of the seats. In Pennsylvania, Republicans tried to impeach the state Supreme Court justices who had struck down a GOP attempt to gerrymander congressional districts in that state. The Trump White House has tried to suppress counts of immigrants for the 2020 census, to reduce their voting power. All political parties maneuver for advantage, but only a party that has concluded it cannot win the votes of large swaths of the public will seek to deter them from casting those votes at all.

The history of the United States is rich with examples of once-dominant groups adjusting to the rise of formerly marginalized populations—sometimes gracefully, more often bitterly, and occasionally violently. Partisan coalitions in the United States are constantly reshuffling, realigning along new axes. Once-rigid boundaries of faith, ethnicity, and class often prove malleable. Issues gain salience or fade into irrelevance; yesterday's rivals become tomorrow's allies.

But sometimes, that process of realignment breaks down. Instead of reaching out and inviting new allies into its coalition, the political right hardens, turning against the democratic processes it fears will subsume it. A conservatism defined by ideas can hold its own against progressivism, winning converts to its principles and evolving with each generation. A conservatism defined by identity reduces the complex calculus of politics to a simple arithmetic question—and at some point, the numbers no longer add up.

Trump has led his party to this dead end, and it may well cost him his chance for reelection, presuming he is not removed through impeachment. But the president's defeat would likely only deepen the despair that fueled his rise, confirming his supporters' fear that the demographic tide has turned against them. That fear is the single greatest threat facing American democracy, the force that is already battering down precedents, leveling norms, and demolishing guardrails. When a group that has traditionally exercised power comes to believe that its eclipse is inevitable, and that the destruction of all it holds dear will follow, it will fight to preserve what it has—whatever the cost.

Adam Przeworski, a political scientist who has studied struggling democracies in Eastern Europe and Latin America, has argued that to survive, democratic institutions "must give all the relevant political forces a chance to win from time to time in the competition of interests and values." But, he adds, they also have to do something else, of equal importance: "They must make even losing under democracy more attractive than a future under non-democratic outcomes." That conservatives—despite currently holding the White House, the Senate, and many state governments—are losing faith in their ability to win elections in the future bodes ill for the smooth functioning of American democracy. That they believe these electoral losses would lead to their destruction is even more worrying.

We should be careful about overstating the dangers. It is not 1860 again in the United States—it is not even 1850. But numerous examples from American history—most notably the antebellum South—offer a cautionary tale about how quickly a robust democracy can weaken when a large section of the population becomes convinced that it cannot continue to win elections, and also that it cannot afford to lose them.

the collapse of the mainstream Republican Party in the face of Trumpism is at once a product of highly particular circumstances and a disturbing echo of other events. In his recent study of the emergence of democracy in Western Europe, the political scientist Daniel Ziblatt zeroes in on a decisive factor distinguishing the states that achieved democratic stability from those that fell prey to authoritarian impulses: The key variable was not the strength or character of the political left, or of the forces pushing for greater democratization, so much as the viability of the center-right. A strong center-right party could wall off more extreme right-wing movements, shutting out the radicals who attacked the political system itself.

The left is by no means immune to authoritarian impulses; some of the worst excesses of the 20th century were carried out by totalitarian left-wing regimes. But right-wing parties are typically composed of people who have enjoyed power and status within a society. They might include disproportionate numbers of leaders—business magnates, military officers, judges, governors—upon whose loyalty and support the government depends. If groups that traditionally have enjoyed privileged positions see a future for themselves in a more democratic society, Ziblatt finds, they will accede to it. But if "conservative forces believe that electoral politics will permanently exclude them from government, they are more likely to reject democracy outright."

Ziblatt points to Germany in the 1930s, the most catastrophic collapse of a democracy in the 20th century, as evidence that the fate of democracy lies in the hands of conservatives. Where the center-right flourishes, it can defend the interests of its adherents, starving more radical movements of support. In Germany, where center-right parties faltered, "not their strength, but rather their weakness" became the driving force behind democracy's collapse.

Of course, the most catastrophic collapse of a democracy in the 19th century took place right here in the United States, sparked by the anxieties of white voters who feared the decline of their own power within a diversifying nation.

The slaveholding South exercised disproportionate political power in the early republic. America's first dozen presidents—excepting only those named Adams—were slaveholders. Twelve of the first 16 secretaries of state came from slave states. The South initially dominated Congress as well, buoyed by its ability to count three-fifths of the enslaved persons held as property for the purposes of apportionment.

Whether the American political system today can endure without fracturing further may depend on the choices of the center-right.Politics in the early republic was factious and fractious, dominated by crosscutting interests. But as Northern states formally abandoned slavery, and then embraced westward expansion, tensions rose between the states that exalted free labor and the ones whose fortunes were directly tied to slave labor, bringing sectional conflict to the fore. By the mid-19th century, demographics were clearly on the side of the free states, where the population was rapidly expanding. Immigrants surged across the Atlantic, finding jobs in Northern factories and settling on midwestern farms. By the outbreak of the Civil War, the foreign-born would form 19 percent of the population of the Northern states, but just 4 percent of the Southern population.

The new dynamic was first felt in the House of Representatives, the most democratic institution of American government—and the Southern response was a concerted effort to remove the topic of slavery from debate. In 1836, Southern congressmen and their allies imposed a gag rule on the House, barring consideration of petitions that so much as mentioned slavery, which would stand for nine years. As the historian Joanne Freeman shows in her recent book, The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, slave-state representatives in Washington also turned to bullying, brandishing weapons, challenging those who dared disparage the peculiar institution to duels, or simply attacking them on the House floor with fists or canes. In 1845, an antislavery speech delivered by Ohio's Joshua Giddings so upset Louisiana's John Dawson that he cocked his pistol and announced that he intended to kill his fellow congressman. In a scene more Sergio Leone than Frank Capra, other representatives—at least four of them with guns of their own—rushed to either side, in a tense standoff. By the late 1850s, the threat of violence was so pervasive that members regularly entered the House armed.

As Southern politicians perceived that demographic trends were starting to favor the North, they began to regard popular democracy itself as a threat. "The North has acquired a decided ascendancy over every department of this Government," warned South Carolina's Senator John C. Calhoun in 1850, a "despotic" situation, in which the interests of the South were bound to be sacrificed, "however oppressive the effects may be." With the House tipping against them, Southern politicians focused on the Senate, insisting that the admission of any free states be balanced by new slave states, to preserve their control of the chamber. They looked to the Supreme Court—which by the 1850s had a five-justice majority from slaveholding states—to safeguard their power. And, fatefully, they struck back at the power of Northerners to set the rules of their own communities, launching a frontal assault on states' rights.

But the South and its conciliating allies overreached. A center-right consensus, drawing Southern plantation owners together with Northern businessmen, had long kept the Union intact. As demographics turned against the South, though, its politicians began to abandon hope of convincing their Northern neighbors of the moral justice of their position, or of the pragmatic case for compromise. Instead of reposing faith in electoral democracy to protect their way of life, they used the coercive power of the federal government to compel the North to support the institution of slavery, insisting that anyone providing sanctuary to slaves, even in free states, be punished: The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required Northern law-enforcement officials to arrest those who escaped from Southern plantations, and imposed penalties on citizens who gave them shelter.

The persecution complex of the South succeeded where decades of abolitionist activism had failed, producing the very hostility to slavery that Southerners feared. The sight of armed marshals ripping apart families and marching their neighbors back to slavery roused many Northerners from their moral torpor. The push-and-pull of democratic politics had produced setbacks for the South over the previous decades, but the South's abandonment of electoral democracy in favor of countermajoritarian politics would prove catastrophic to its cause.

today, a republican party that appeals primarily to white Christian voters is fighting a losing battle. The Electoral College, Supreme Court, and Senate may delay defeat for a time, but they cannot postpone it forever.

From January/February 2009: Hua Hsu's cover story on the end of white America

The GOP's efforts to cling to power by coercion instead of persuasion have illuminated the perils of defining a political party in a pluralistic democracy around a common heritage, rather than around values or ideals. Consider Trump's push to slow the pace of immigration, which has backfired spectacularly, turning public opinion against his restrictionist stance. Before Trump announced his presidential bid, in 2015, less than a quarter of Americans thought legal immigration should be increased; today, more than a third feel that way. Whatever the merits of Trump's particular immigration proposals, he has made them less likely to be enacted.

For a populist, Trump is remarkably unpopular. But no one should take comfort from that fact. The more he radicalizes his opponents against his agenda, the more he gives his own supporters to fear. The excesses of the left bind his supporters more tightly to him, even as the excesses of the right make it harder for the Republican Party to command majority support, validating the fear that the party is passing into eclipse, in a vicious cycle.

The right, and the country, can come back from this. Our history is rife with influential groups that, after discarding their commitment to democratic principles in an attempt to retain their grasp on power, lost their fight and then discovered they could thrive in the political order they had so feared. The Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, criminalizing criticism of their administration; Redemption-era Democrats stripped black voters of the franchise; and Progressive Republicans wrested municipal governance away from immigrant voters. Each rejected popular democracy out of fear that it would lose at the polls, and terror at what might then result. And in each case democracy eventually prevailed, without tragic effect on the losers. The American system works more often than it doesn't.

The years around the First World War offer another example. A flood of immigrants, particularly from Eastern and Southern Europe, left many white Protestants feeling threatened. In rapid succession, the nation instituted Prohibition, in part to regulate the social habits of these new populations; staged the Palmer Raids, which rounded up thousands of political radicals and deported hundreds; saw the revival of the Ku Klux Klan as a national organization with millions of members, including tens of thousands who marched openly through Washington, D.C.; and passed new immigration laws, slamming shut the doors to the United States.

Under President Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic Party was at the forefront of this nativist backlash. Four years after Wilson left office, the party faced a battle between Wilson's son-in-law and Al Smith—a New York Catholic of Irish, German, and Italian extraction who opposed Prohibition and denounced lynching—for the presidential nomination. The convention deadlocked for more than 100 ballots, ultimately settling on an obscure nominee. But in the next nominating fight, four years after that, Smith prevailed, shouldering aside the nativist forces within the party. He brought together newly enfranchised women and the ethnic voters of growing industrial cities. The Democrats lost the presidential race in 1928—but won the next five, in one of the most dominant runs in American political history. The most effective way to protect the things they cherished, Democratic politicians belatedly discovered, wasn't by locking immigrants out of the party, but by inviting them in.

Whether the American political system today can endure without fracturing further, Daniel Ziblatt's research suggests, may depend on the choices the center-right now makes. If the center-right decides to accept some electoral defeats and then seeks to gain adherents via argumentation and attraction—and, crucially, eschews making racial heritage its organizing principle—then the GOP can remain vibrant. Its fissures will heal and its prospects will improve, as did those of the Democratic Party in the 1920s, after Wilson. Democracy will be maintained. But if the center-right, surveying demographic upheaval and finding the prospect of electoral losses intolerable, casts its lot with Trumpism and a far right rooted in ethno-nationalism, then it is doomed to an ever smaller proportion of voters, and risks revisiting the ugliest chapters of our history.

Two documents produced after Mitt Romney's loss in 2012 and before Trump's election in 2016 lay out the stakes and the choice. After Romney's stinging defeat in the presidential election, the Republican National Committee decided that if it held to its course, it was destined for political exile. It issued a report calling on the GOP to do more to win over "Hispanic[s], Asian and Pacific Islanders, African Americans, Indian Americans, Native Americans, women, and youth[s]." There was an edge of panic in that recommendation; those groups accounted for nearly three-quarters of the ballots cast in 2012. "Unless the RNC gets serious about tackling this problem, we will lose future elections," the report warned. "The data demonstrates this."

But it wasn't just the pragmatists within the GOP who felt this panic. In the most influential declaration of right-wing support for Trumpism, the conservative writer Michael Anton declared in the Claremont Review of Books that "2016 is the Flight 93 election: charge the cockpit or you die." His cry of despair offered a bleak echo of the RNC's demographic analysis. "If you haven't noticed, our side has been losing consistently since 1988," he wrote, averring that "the deck is stacked overwhelmingly against us." He blamed "the ceaseless importation of Third World foreigners," which had placed Democrats "on the cusp of a permanent victory that will forever obviate [their] need to pretend to respect democratic and constitutional niceties."

The Republican Party faced a choice between these two competing visions in the last presidential election. The post-2012 report defined the GOP ideologically, urging its leaders to reach out to new groups, emphasize the values they had in common, and rebuild the party into an organization capable of winning a majority of the votes in a presidential race. Anton's essay, by contrast, defined the party as the defender of "a people, a civilization" threatened by America's growing diversity. The GOP's efforts to broaden its coalition, he thundered, were an abject surrender. If it lost the next election, conservatives would be subjected to "vindictive persecution against resistance and dissent."

Anton and some 63 million other Americans charged the cockpit. The standard-bearers of the Republican Party were vanquished by a candidate who had never spent a day in public office, and who oozed disdain for democratic processes. Instead of reaching out to a diversifying electorate, Donald Trump doubled down on core Republican constituencies, promising to protect them from a culture and a polity that, he said, were turning against them.

When Trump's presidency comes to its end, the Republican Party will confront the same choice it faced before his rise, only even more urgently. In 2013, the party's leaders saw the path that lay before them clearly, and urged Republicans to reach out to voters of diverse backgrounds whose own values matched the "ideals, philosophy and principles" of the GOP. Trumpism deprioritizes conservative ideas and principles in favor of ethno-nationalism.

The conservative strands of America's political heritage—a bias in favor of continuity, a love for traditions and institutions, a healthy skepticism of sharp departures—provide the nation with a requisite ballast. America is at once a land of continual change and a nation of strong continuities. Each new wave of immigration to the United States has altered its culture, but the immigrants themselves have embraced and thus conserved many of its core traditions. To the enormous frustration of their clergy, Jews and Catholics and Muslims arriving on these shores became a little bit congregationalist, shifting power from the pulpits to the pews. Peasants and laborers became more entrepreneurial. Many new arrivals became more egalitarian. And all became more American.

RELATED STORY

Americans Aren't Practicing Democracy Anymore

By accepting these immigrants, and inviting them to subscribe to the country's founding ideals, American elites avoided displacement. The country's dominant culture has continually redefined itself, enlarging its boundaries to retain a majority of a changing population. When the United States came into being, most Americans were white, Protestant, and English. But the ineradicable difference between a Welshman and a Scot soon became all but undetectable. Whiteness itself proved elastic, first excluding Jews and Italians and Irish, and then stretching to encompass them. Established Churches gave way to a variety of Protestant sects, and the proliferation of other faiths made "Christian" a coherent category; that broadened, too, into the Judeo-Christian tradition. If America's white Christian majority is gone, then some new majority is already emerging to take its place—some new, more capacious way of understanding what it is to belong to the American mainstream.

So strong is the attraction of the American idea that it infects even our dissidents. The suffragists at Seneca Falls, Martin Luther King Jr. on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, and Harvey Milk in front of San Francisco's city hall all quoted the Declaration of Independence. The United States possesses a strong radical tradition, but its most successful social movements have generally adopted the language of conservatism, framing their calls for change as an expression of America's founding ideals rather than as a rejection of them.

Even today, large numbers of conservatives retain the courage of their convictions, believing they can win new adherents to their cause. They have not despaired of prevailing at the polls and they are not prepared to abandon moral suasion in favor of coercion; they are fighting to recover their party from a president whose success was built on convincing voters that the country is slipping away from them.

The stakes in this battle on the right are much higher than the next election. If Republican voters can't be convinced that democratic elections will continue to offer them a viable path to victory, that they can thrive within a diversifying nation, and that even in defeat their basic rights will be protected, then Trumpism will extend long after Trump leaves office—and our democracy will suffer for it.

Juan