| 7:34 PM (1 hour ago) |    | ||

| ||||

Monopoly Round-Up: Lina Khan, Pharma Middlemen and "Tasty Rebates"The FTC sued the key middlemen of big pharma. Plus more on the Wall Street campaign to fire Lina Khan, and the ad world prepares for Google's break-up.

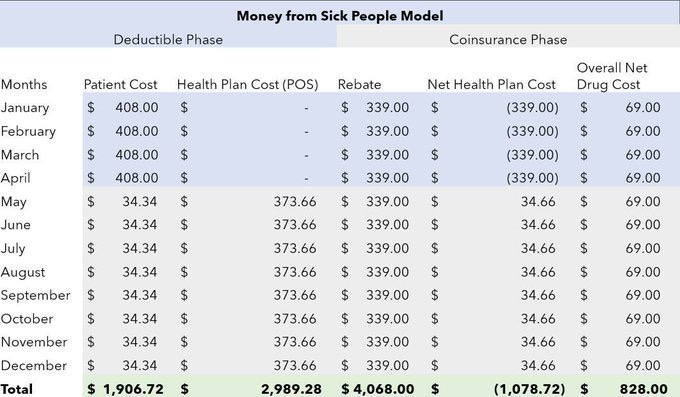

This week's monopoly round-up has some awesome stuff, as usual. For paid subscribers, I'll have the good news and bad news of the week, plus a section on the Google trial. But first I want to focus on a big deal lawsuit from the FTC. On Friday, the Federal Trade Commission sued the three middlemen who administer 80% of all prescriptions in America - Caremark, Express Scripts, OptumRx - for rigging the market for insulin. Americans buy somewhere between $500 billion and $700 billion of pharmaceuticals a year. And while this complaint is targeted at insulin, the goal is much broader. As FTC official Rahul Rao put it, the FTC is hoping for "a fix that could ripple beyond the insulin market and restore healthy competition to drive down drug prices for consumers." On one level, the FTC is bringing a lawsuit because certain prices for insulin are far too high. As the commission put it, "Insulin medications used to be affordable. In 1999, the average list price of Humalog—a brand-name insulin medication manufactured by Eli Lilly—was only $21… By 2017, the list price of Humalog soared to more than $274—a staggering increase of over 1,200%." The other major forms of insulin have also seen such increases. A key reason is that much cheaper forms of this medicine, which was first invented in 1922, are being kept off the market. But there are a few wrinkles here. First, the FTC isn't actually suing Eli Lilly, the maker of Humalog that appears to be doing the over-charging. Nor is it suing Novo Nordisk or Sanofi, the other two main insulin producers, though the commission did go out of its way to state that it might bring litigation in the future against them. It gets a bit more odd. The FTC isn't alleging that everyone is paying too much for insulin, only "certain patients" who are forced to pay higher out-of-pocket costs. Who in particular? Well, those "with deductibles and coinsurance." But aren't prices going up? Well, sort of. List prices are going up. In fact, the FTC is suing the middlemen responsible for selling insulin, what are called pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs. The claim is that the PBMs and the producers themselves are in a loose cartel, jointly raising secret prices to specifically hit people who must pay cash out of pocket for insulin. Basically, like everything else in America, since 2012, a set of monopolists have turned buying pharmaceuticals into a weird financial game, with opaque rules and fees. That's why medical billing, with things like deductibles, coinsurance, copays, and the like, is so annoying. It's designed to extract. And this scheme shows how. Let's start with what is different today about medical markets. And it's not high pharma prices, which have been around at least since the 1950s. For instance, from 1959-1963, the great anti-monopolist Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver held hearings in the Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee on the abuses and corruption of big medicine. Many of the issues were the same then as they are now, such as pharma playing patent games to prevent cheaper generic drugs from reaching the market. But in many ways, that era was the golden age, with new effective drugs for big broad conditions coming out regularly. Though drugs were pricey, it wasn't that bad. One scandal referenced by Kefauver was a steroid hormone cost 1.7 cents a pill being sold at 18 cents a pill, which is about two dollars in current money. Basically, America was in the upper tier of pricing internationally, but it was more an annoyance and outrage in a middle class country, nothing more. Something is different today. Prices are much higher, for sure; the median list price of a new pharmaceutical in 2023 was $300,000. But the main difference is that most of us get our drugs through health insurance plans, and due to policy under George W. Bush starting in the early 2000s, health insurance plans began creating these things called high deductibles. That is, insured patients have to pay cash out of pocket until they reach a cap, usually a few thousand dollars for an individual, and then the insurance company starts paying. Over time, and with encouragement from President Obama, such high deductible plans became common, and now even many insured Americans are having trouble paying for pharmaceuticals out of pocket. Deductibles, or what's broadly known as 'cost sharing,' are critical to understanding the cost of pharmaceuticals today. Because what's happened over the last twenty years is something fundamentally new. Pharmaceutical companies, health insurance companies, and even large employers now work together to get patients to pay out of pocket for drugs, and then split the amount among themselves. The way they do this is by hiding the price of pharmaceuticals. There is the sticker price, called a 'list price,' but few people really pay it. Think of the list price as the price of a dress sold by a low end department store that is always having a sale where it offers an 85% discount. Few pay the full amount, since it's always on sale, by varying amounts. Since the FTC case involves insulin, let's go to the sticker price of Sanofi's Lantus brand insulin, which according to think tank Brooklyn46, had a $403 list price in 2019 for a month supply. Sanofi is in competition with Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly to get its insulin in front of patients. Now in most countries, they would compete by lowering their price or improving their product, because the agent for the buyer, usually the government, is paid by taxpayers. But in the U.S., the key agent for the buyer is a PBM. Why do PBMs exist? Well making a list of all pharmaceuticals necessary to treat conditions and ensuring payment between patients, pharma companies, and pharmacies is a complex endeavor. PBMs make the system work on behalf of insurance companies. Today, three PBMs control what drugs insurance companies offer their patients, as well as the prices. The list of said drugs is known as a formulary. In 2012, the three dominant PBMs, who control 80% of drug dispensing, started to demand rebates, or kickbacks, from pharmaceutical companies, with the threat they would exclude their drug from their formularies if they didn't get it. If your drug isn't on a formulary, it basically cannot be sold to patients, it's like taking it off the shelf. Think about what this dynamic means. Most people think that other country's have lower pharmaceutical prices because the government does the negotiating. But the truth is not about public vs private sectors. In other countries, the agents for the buyers are paid by the buyers to lower prices. In America, PBMs are supposed to be representing buyers, but they are paid by the sellers through kickbacks. No wonder they want higher prices! By 2019, Sanofi was giving OptumRx, one of the biggest PBMs, 80% of the list price of Lantus just to be the preferred insulin for its patients. That's just $64 going to Sanofi for the drug, and $339 going to OptumRx as a kickback. Now, you might think that's not a big deal. I mean, a PBM works for an insurance company, and you would think insurance companies have an incentive to keep pharma prices low. After all, insurance companies take a monthly payment from patients, and then pay for most medical expenses. A drug cost is an expense, therefore they'd like that to be lower. So you'd imagine that the $339 kickback is just a way of lowering the price to the patient. But here's where it gets nasty. Remember what I wrote about deductibles? That's when a patient has to pay the price of their care, up to a cap. In the case of Lantus, the patients are paying the list price out of pocket. But the rebate stays with the PBM. And today, the big PBMs are owned by the big insurers; OptumRx is part of UnitedHealth Group. CVS/Aetna owns Caremark, and Cigna owns Express Scripts. So what we're really talking about is the insurance companies, who should be paying for the medicine that their customers need with revenue from monthly premium payments, are forcing their customers to pay inflated prices for medicine and then getting a kickback from the pharma companies. That's why insurance companies often don't like lower prices for pharmaceuticals, it would take away their rebating profits. Here's a chart from Antonio Ciaccia at 46Brooklyn, the think tank that figured a lot of this scandal out. For a full year course of insulin, you can see that a patient is paying $1,906.72 in cash out of pocket, OptumRx is receiving $1,078.72, and Sanofi is getting $828. Since OptumRx is splitting that with an insurance company, or may even be your insurance company since it's owned by UnitedHealth, that means the insurance company is getting money from its patients when it should be paying money on behalf of patients. It gets even more insidious. You might think that large employers, who have benefit departments managing hundreds of millions or billions in pharma spending, would be looking out for their employees when doing plan selection. But two class action lawsuits, one against Wells Fargo and one against Johnson & Johnson by a law firm called Fairmark, show that they are not. The reason, though it's not stated in the suits, is likely that they are getting kickbacks themselves, or that the benefit consultants and insurance brokers like Aon and Willis Towers Watson are receiving benefits. It's rebates all the way down, in other words. I'm reminded of a scene in the movie Lord of War, where an arms dealer named Yuri Orlov is working with a corrupt Soviet general after the fall of the USSR to sell the contents of his arms depot. The general asks what happens if someone tries to audit what they are doing. The response from Orlov is "then we'll cut them in." That's how PBMs work. They aren't just middlemen, they are allocators of what really looks perilously close to organized crime loot to an series of conspirators, from pharmaceutical firms to insurers to benefit consultants to large employers. To give you a sense of the scale, Kentucky in 2021 eliminated these PBMs from its Medicaid program, and saved $283 million in just a few years. And that's just one small part of one small state's health care spending. Enter FTC Chair Lina Khan. A few months ago, the FTC released a report on PBMs, one cited repeatedly in July by dozens of members of Congress in an oversight hearing with the leaders of the PBMs. In response, Express Scripts did something odd. They hired a Reaganite lawyer named Rick Rule, famous as the youngest lawyer ever to be confirmed to run the Antitrust Division in 1986. (He wasn't the youngest, Bob Bicks under Eisenhower was, and Bicks never got confirmed. Unlike Rule, Bicks took the job seriously.) Earlier this week, Rule repped Express Scripts, and sued the FTC for defamation over the report, demanding its retraction. (The suit is crazy and likely be tossed as frivolous, but if you want a good analysis of the allegations and the corrupt economist behind them, a guy named Dennis Carlton, here you go.) But as it turns out, it wasn't the report they were worried about, because the FTC was coming after their whole business model. And that gets us to the insulin lawsuit, which has been a long time coming. In 2021, FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra started the ball rolling by writing an opinion attacking PBMs. In 2022, Chair Khan issued a policy statement on insulin and price discrimination. But still, the story I told above, the idea of PBMs as middlemen who organize an entire organized syndicate, was theory. The FTC just turned it into a legal case, suing not the insulin makers, but the middlemen who "systemically excluded… lower list price insulins…in favor of high list price, highly rebated insulin products." Indeed, the FTC quotes one executive noting that their strategy let them continue to "drink down the tasty … rebates." And the target was those with deductibles and coinsurance, who "may pay more out-of-pocket for their insulin drugs than the entire net cost of the drug to the commercial payer." That's the chart from 46Brooklyn above. (The FTC also named a series of subsidiaries in foreign countries where the PBMs hide their rebate monies.) The FTC isn't using its authority under the Sherman Act, but a special authority to bar "unfair methods of competition," known as Section 5. It is also doing a case under its administrative court, so that it'll move quickly and not be bogged down for years in a Federal docket. The specific claims are that the Big Three paid off manufacturers to "inflate insulin list prices," they sought to restrict "access to more affordable insulins," and they shifted "the cost of high list price insulins to vulnerable patient populations." Politicians and media outlets across the spectrum praised the move, from Democraitc Montana Senator Jon Tester to House Oversight Chair James Comer. It's on 60 Minutes, the New York Times, the Washington Post, CNBC, CNN, so forth. It hit the stocks of these firms, which are Fortune 20 firms. The big implication here isn't just about insulin, though that's significant. In some ways, a few years ago, the big guys already realized that costly insulin was just too big a PR headache, and started to just give up on that category, since a new generation of treatments is around the corner. That's why they increasingly give out coupons, and are not fighting the $35 price caps. The problem for the big three is that they operate this way for virtually every major medication they can, driving up list prices and overall costs across the board. If the FTC gets relief on insulin that says these kinds of secret rebates are illegal, or that PBMs have to give equal rebates to everyone, then it radically upends how pharmaceuticals get sold in America. All of a sudden, the PBMs who are supposed to be bargaining for prices to come down will start doing that, instead of bargaining to raise them. In truth, there's nothing new under the sun. In 1914, Louis Brandeis wrote a book called Other People's Money And How The Bankers Use It, pointing out that the most powerful position in an economy is to be a steward of someone else's money, without any restrictions on conflicts of interest. Today, we could sub in the word PBMs for Bankers and it would still work. Because of the philosophical change we've orchestrated, finally our enforcers get that. And now, read on, to see how a different group of enforcers are faring in the campaign to break up Google. (TLDR it's going well!) After that, there's the good and bad news of the week... |

― The Lincoln Project

No comments:

Post a Comment